Episode 1:

Cosmovision and Human Sacrifice

Early Mesoamerican cultures like the Mayans, the Olmecs, and later the Aztecs remain shrouded in mystery. The Spanish who arrived in the 1500's apparently tried their best to bury and erase these mysteries further. But what’s been discovered indicates they were highly advanced civilizations that were intensely engaged with the cosmos and their living environment. They believed certain actions, like bloodletting or human sacrifice, could advance their world. But were their human sacrifice practices really any more strange or barbaric than other traditional notions of sacrifice?

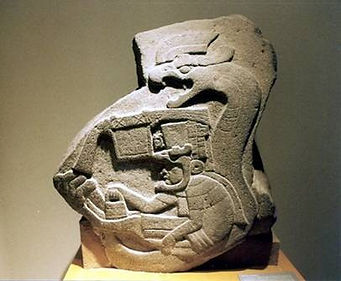

Ross Chambless: One of the earliest discoveries of a stone idol depicting Quetzalcóatl – the “Plumed Serpent” – was unearthed at the ancient Olmec site of La Venta, in the Mexican state of Tabasco. The archeologists who found it labeled it “Stela 19."

Susan Vogel: It's a pretty interesting image. It appears to show a person leaning, sitting against a plumed serpent. The serpent sort of nestles across the person's back. The person has some sort of helmet or a headdress on and it's holding a basket, which is thought to hold copal, an incense.

Ross: The Olmec were among the first civilizations to develop in the Americas. This “mother culture” of Mesoamerica formed about some 1500 to 400 years before the birth of Christ by the Western Calendar. But it turns out that they had their own calendar. Probably the world’s first Long Count calendar tracking days, months and years.

Susan: At this time in Mesoamerican history there’s a lot up for grabs. People are constantly analyzing these objects and coming up with different ideas of what they represent. So sometimes when we teach this time period, the students are frustrated because we can’t say definitively what a lot of things are. And again, the research is continually changing.

Ross: Quetzalcóatl represents the worldview, of these ancient Mesoamericans. One such view has come to be known as cosmovision.

Fanny Blauer: For me, it’s those beings that connect god with men; their holy gods, meaning their gods' representatives on Earth. The jaguar represented for the Olmecs the ruler of the darkness, meaning the best warriors and the highest classes in their society. The snakes represented the territorial world and mankind's knowledge. So when we see those elements of wisdom and warriors and the strongest rulers, and the men combined, within this piece, it’s what I call cosmovision. All the elements of the universe are comprised in what a human is.

This “Aztec Stone of the Sun” is a full-size replica in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. The Aztecs believed that as the Sun was the source of all life, it required the sacrifice of blood and of lives to sustain it. The Stone of the Sun weighs more than 20 tons and is 12 feet in diameter. It was installed in the ceremonial center of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, until Cortés threw it down and buried it during the time of the conquest. It was rediscovered in 1790, and now stands in the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

Luis Lopez: To my understanding, the cosmovision comes as a couple of different things. One is definitely there's a duality: the feathered serpent is Quetzalcóatl. But he does have his counterpart in the Mesoamerican belief system. Both of these deities are required for certain things to happen. You’ll see that pattern throughout pretty much everything. Also the idea that in these cultures, many times you see humanity and these other ideas all interconnected at the same time. Today, for example, people think of the afterlife as something that once life ends, then you enter this realm. It’s not that way during this time period. It’s all happening at the same time. It’s all interconnected.

Ross: Stop and think about that for a moment. This life, and the afterlife - all interconnected. Apparently, this mindset shaped everything about the day-to-day lives of these people. We know from textual and archeological records that it influenced everything down to how they organized their lives and designed their rituals, their customs, and their cities. Fanny says that today, in many ways, we can still see this worship of ancestors in Mexican society.

Fanny: Everything that they were able to contemplate, during the day or night, the natural phenomena – they were able to connect that with a vision that there was this cosmos energy that was producing and making things happen. Based on that, they created the idea of their society. They influenced the views of their society based on what the cosmos was saying at a certain time of the year. It wasn’t necessarily a year of 12 months, right. But it was a time they created based on the farming, or the harvesting, or the growing. They created political and religious practices based on what they saw. So, everything was connected to what the Earth was providing to these humans. And they were able to create religion based on how they saw the sky at night for example – the shapes of the stars. They were able to create symbolism based on the formations of the mountains, the sun, and the rain, and how the plants were growing. So, it’s all connected with the cosmos.

Ross: So now this fundamental understanding of cosmovision, this is a sort of worldview that persisted from what we believe, from the Olmecs up through the Aztecs, to the Mayas. We are talking generally about Mesoamerican people.

The Aztecs used a rubber ball for a game that was a revision of an ancient Mesoamerican game. It was not just entertainment, but also had political and religious purposes as well.

Susan: The Olmecs are considered the mother culture. One of their characteristics is that they believed that the Olmec people were the product of a union between a woman and a jaguar. So, one thing I think interesting is that we don’t have jaguars here in Utah, and I've never had the privilege of encountering one, but they are the top of the food chain. In Mesoamerica, they are probably very scary to these indigenous people and also probably pretty awesome as well. They love the water. They are a feline that loves the water, which makes them extremely versatile. If you are going to choose an animal or a reptile to protect you, you might choose a jaguar. The other thing about the Olmecs is their name, which was given to them much later, indicates "the rubber people" or the "people who have rubber." They were the first people to harvest it and use the rubber. If you google "rubber," this is where it was first used. They used it in balls. They had ball courts. They also used it to water-proof vessels, which was hugely important thing in this time.

The History Channel's In Search of History series "The Aztec Empire" (2005)

Ross: It turns out, another thing that this ancient Mesoamericans are known for is something called the "bloodletting" – the act of piercing yourself or someone else as a way to influence the cosmos, as an offering.

Susan: It’s interesting when you think about the beginning of time, and how people are trying to understand the universe: if the Sun comes up – and maybe it came up after you a few drops of blood fell on the ground – you might drop a few more the next morning.

Ross: Some think this notion of bloodletting was connected to the practice of human sacrifice – which is definitely something that’s continued to fascinate people, even if it’s been embellished.

A scene depicting an Aztec human sacrifice in Mel Gibson's 2006 film Apocalypto.

Ross: I remember seeing Mel Gibson’s film Apocalypto in the mid-2000's and I have to say I was pretty shocked and disturbed. It depicts an Aztec ritual human sacrifice. A man, a captured enemy, is held down on an altar while a priest cuts out his heart and hold it up to the cheers of thousands of Aztecs at the base of the temple. Some archeologists speculate the Aztecs may have sacrificed around 20,000 victims a year. What was the purpose of this? There are gruesome illustrations people have drawn up, imagining these bloodletting rituals.

Luis: Well, according to stories and a couple of codices, it is believed that the Mexica, which were the primary group of the Aztec Empire, practiced human sacrifice. It was tied into their beliefs, these ideas that we have to please the gods. In my experience, there has been some debate as to whether this was practiced throughout Mesoamerica. A professor of mine who is Nahuatl, a native speaker, says there is no record of his people practicing that. But it is something we hear pretty often. I think the idea of sacrifice is something that has transcended from that time period – not human sacrifice – let me clarify that we’re not cutting people open. It’s the idea that sacrifice is part of life. It’s something we still practice, and we know when we go through difficult times, it’s necessary to transition into the next moment in our lives.

Ross: The Spanish – specifically Cortés – made reference to human sacrifices in his letters to Charles the V, King of Spain, about Tenochtitlan.

Fanny: He clearly talks that people would be laying down, and cutting in the middle, and grabbing the heart and dedicating this heart. However, it’s important to understand whether it happened or not, the act of sacrifice was not to enjoy the pleasure of killing. The way I see it, again, it’s a connection with cosmovision. We are [living] entities. We are human beings who are alive, who are able to produce life and in order to produce life we have to give life. It’s a cycle of life. Their idea, how I understand it, is that they had to feed life to their gods so that they could continue producing for them. It was an honor to offer blood or the most important organ in the human body, such as the heart, so that the gods would continue to feed us. It’s a cycle of life.

The practice of human sacrifice was not unique to Mesoamericans. The Greeks also engaged in human sacrifice. This graphic depiction of the sacrifice of Polyxena during the Trojan War, (c. 570-550 BCE) was painted on a vase.

Susan: It is more known – human sacrifice in Mesoamerica is probably more high profile because it is so fascinating. The cultures are so fascinating; the monumentality of the pyramids. And it is just so fascinating to learn about these cultures. But historically, it’s not a unique thing. I just traced my DNA to Scandinavia – big surprise, with a little bit of Iberian, thanks to those Vikings who got around. And they engaged in human sacrifice. The Greeks engaged in human sacrifice to make the wind blow. All kinds of cultures engaged in that. I think I read that they also found evidence of it at Monk’s Mound in Illinois – that's one of the pyramids that we call "a mound," from about 950 to 1100 common era. So, it overlapped up with the time that this was going on in Mesoamerica.

Ross: If I reflect about how this gruesome stories and images make me feel, there is definitely a part of me, maybe that same part that those early Spanish explorers like Cortés felt, that feels these human sacrifices and this bloodletting were just acts of savagery that perhaps deserved to be wiped out. But with that, I'm imposing my own cultural modern perception on all this. I'm trying to open my mind to this whole cosmovision thing.

Fanny: It’s a subject that is very sensitive still, and highly criticized. Especially entering into the subject of religion for example, and how the Spanish arrived in Mexico and saw these horrible sacrifices of people, grabbing the heart and dedicating it to their gods of the sun or the rain or the moon. But when I think about it, the continuation of that idea, in a different way, is still the same. The Spanish arrived, and they taught that there was this man who died on the cross. And the image of the Christ is not the image of (I'm going to compare it with), the Christ of the LDS Church for example – the idea of the resurrection, so this white image of Jesus raising, right? But the image the Spanish taught was of this Christ, bloody body. And he died for you. And their representation of connecting with this god is through the holy communion. We drink wine and take a piece of bread. And the wine represents the blood. It’s exactly the same thing.

Luis: It's just the lens that we are viewing this through. We tend to look at this culture through our current lens. We have to check that at the door when we look at this; because obviously, we have influences that went around at a time. So, absolutely sacrifice was definitely present both in Mesoamerica and modern cultures.

Susan: I grew up Methodist and we didn't have the bloody cross or the bloody Jesus. And we thought that that was horrifying. But we did learn that God sacrificed his only son so that we can live.

~ ~ ~

Credits:

Thanks to our commentators Susan Vogel; Fanny Guadalupe Blauer; Luis Lopez; Episode produced and edited by Ross Chambless; Thanks to KCPW 88.3 FM for the studio space; Music credit: Ricardo Lozano and Jorge Ramos. This podcast is made possible thanks to Utah Humanities.