Episode 20:

From Neither Here Nor There

Ni De Aquí Ni De Allá

Life in Utah can be hard for Latinos where the majority of the population is White. Latinos in Utah sometimes experience subtle and overt racism and discrimination. At the same time, Mexican Americans can also feel like outsiders when they travel to Mexico. In this episode we examine this dichotomy and also explore the work of Linda Vallejo, a Chicana artist from California, who produces art to challenge cultural normalization and implicit bias about skin color with her series "Make ‘Em All Mexican." She also challenges the internalized negative attitudes some Latinos have about having brown skin.

Ross Chambless: What does it feel like to be Latino in Utah, as opposed to being Latino in Southern California, or Texas? What does it feel like to have brown skin in a place where most people – at least for now – mostly have white skin? This is a question that for me – as someone with white skin – I’ve been pondering recently. And it’s a question I posed to some of my Utah Latino friends. Here is Jorge Rodriguez.

Jorge Rodriguez: All right, for me, this is an interesting question. I’ve only lived in Utah for 15 years now… I didn’t realize I had a skin color until I moved to Utah. I don’t know how else to put it. I lived in L.A. a long time. I’ve lived in Texas and Hawaii. And everywhere I went I knew I wasn’t necessarily from there. But I never felt as out of place in place as I’ve felt in Utah. It’s the first place where I’ve been pulled over for driving. The first place where I’ve been stared at for walking down the street. It’s the first place where I’ve lived at for more than a couple years and I still see people huddling their kids closer to them. It’s interesting to me because I know who I am, but they don’t. All they have are the limited experiences and portrayals of someone who is not me. So, being in Utah is a unique thing for me because I now identify more strongly as a Chicano than I would have otherwise. I think part of the reason I call myself a Chicano so much now and really adhere to the culture is this is my response to those reactions. To that lack of representation and lack of familiarity about people like myself.

Ross: So, this is Nuevas Voces, of course, This is Episode 20. And in this one we’re talking about it means to be viewed as an outsider - or as not belonging - because of one’s skin color. Specifically, how it can feel to be Latino in Utah. We’ll also be talking about how art can turn all of it upside down. We’ll look at the work of one contemporary Chicana artist Linda Vallejo who has been transforming established images of white people, and challenging society’s norms and assumptions about skin color and race when it comes to brown skin and white skin. Her work is titled “Make ‘Em All Mexican.” But, before we get to that, let’s first consider this idea about not belonging.

Scene from the 1997 film Selena

Ross: There’s a film called Selena – it’s a 1997 biopic drama about the life of the late Chicana pop singer. In one memorable scene, Selena, played by Jennifer Lopez, is talking with her father, played by Edward James Olmos, about what it means to be Mexican American.

Scene from Selena:

Father: “Being Mexican American is tough. Anglos jump all over you if you don’t speak English perfectly. Mexicans jump all over you if you don’t speak Spanish perfectly. We’ve got to be twice as perfect as anyone else.

Selena: (laughs)

Father: Why are you laughing? I’m serious. Our family has been here for centuries. And yet they treat us as if we just swam across the Rio Grande. I mean, we got to know about John Wayne, and Pedro Infante. We got to know about Frank Sinatra and Augustin Lara. We got to know about Opra and Christina. Anglo food is too bland, and when we go to Mexico we get the runs. Now, that to me is embarrassing.

Selena: No, dad!

Father: Japanese Americans, Italian Americans, German Americans, their homeland is on the other side of the ocean. Ours is right next door, right over there. And we got to prove to the Mexicans how Mexican we are, and we got to prove to the Americans how American we are. We got to be more Mexican than the Mexicans, and more American than the Americans at the same time. It’s exhausting!”

Ross: Does this dichotomy about not really belonging anyplace feel familiar? If you’re a person of Mexican descent, have you ever been made feel like an outsider when visiting Mexico? Or has anyone ever assumed you were an outsider in your own country – the United States? It’s this feeling of being of two worlds, but at the same time, not belonging in either place. It seems like everyone might be able to share a story.

Gloria Gonzalez Cook: I’d like to say having grown up here 60 years ago, there were obviously very few Latino people. Walking into a store people turn around and stare at you. One of the reasons I hyphenated my name was because when I got married, my husband is not Hispanic, his name is Cook. I would call someone up looking for an apartment and introduce myself, I’m a student, my husband works at the U, and I don’t sound like I’m from anywhere else. But when they would meet me it was a completely different story. Oh, I’m so sorry, there’s a long line waiting for the apartment. This was in the ‘70s. And that’s when I said I feel like I’m trying to hide myself. I don’t want to hide myself. I want them to know who I am upfront, and then they can decide how they feel about me then. When we went to New York I hyphenated my name. As I said, I went to West High, but back then there were very few Hispanics at West High. We were a true minority. The minority population in Utah was 2 percent. That included Hispanics, blacks, Native Americans, Asians, and everybody.

Utah's population is growing more diverse.

Ross: Today Utah’s minority population is roughly 21 percent. And the fastest growing minority population are Latinos, who make up about 15 percent of the state’s demographics, or another way to say it is 1 in every 7 Utahns are Hispanic. That’s a significant part of our state’s population. But as someone who grew up in Utah, and have lived here for about 40 years, it didn’t used to be so diverse. And frankly, I never felt more white than when I left Utah and lived in Texas for a few years during college, a place with much more ethnic and racial diversity. I’ve gradually figured out that part of white privilege – not having to think about it, or be conscious of it. Living in Utah, I was totally oblivious to the experiences of people of color. I didn’t have experiences like Luis’.

Luis: So, I came to Utah at the age of 17, just before my senior year of high school. I came from Garden Grove California to Lehi, Utah. Where I was there was a little less of a Mexican population, but also Filipino, Vietnamese, so still had diversity in that regard. When I came to Lehi I was about 5 kids who self-identified as Latino. I'm very grateful for the Carreño family out in Lehi. It was one of the safe spaces I could hang out in. It was ok to play music until 2 or 3 in the morning, as long as you’re here. So, I didn’t feel that out of place amongst communities of color. It was actually when I was in more white spaces that I felt a difference. And as others mentioned, it was then that I was being looked at some exotic creature. Or, I walk in a store and for the person before they say welcome to such and such let me know if you need help. And when I walk in, ‘what can I get for you?’ Things like that – those little micro-aggressions, micro-assaults. It wasn’t when I was in mostly Chicano communities, it was when I was in mostly white communities that I felt that change.

Ross: This is Jorge Rodríguez.

Jorge: Another thing that I thought was really interesting was, Utah is the first place where anybody asked me if I had a Greencard or would ask me why I didn't have an accent. It's insane, I mean, I would be in the University telling about my time in the military and "wait, but do you have a Greencard? You speak English so well". At the time, it was such a strange question to have asked me, because I was well over 30 years old and when someone would ask me that for the first time, its was crazy to me. It has definitely been an interesting place to live in.

Scene from Cheech Marin's (of cheech and Chong Fame) 1987 film Born In East L.A.

Ross: This song is from 1987 film Born in East L.A.

Gloria: I had an experience. A couple, actually twice. I’ve been stopped by immigration. Once when I was getting off a bus. I’d been in Mexico and traveling from Tucson, but it was in Las Vegas and trying to get back to Salt Lake. The immigration boarded the bus and wanted your ID. But the other time, I had gone to L.A. and spent a couple of days with my aunt and uncle in the San Fernando Valley. I was walking to the store, and this black car pulls up to the curb and two men in black suits get out and stop me. They wanted to see ID and know where I’m from. Then they heard me talk. They asked, where did you go to high school? West High, Salt Lake City. But I thought I am first and second generation U.S.-born. But my family has been here a hundred years. I do not look like someone who just crossed the border. And I do not mean to stereotype anybody, but I do not look like that. When I go to Mexico they know I’m an American. But to have American immigration stop me. And it’s happened twice in my life.

American Gothic, meet Mexican Gothic (by Linda Vallejo)

Ross: So, how does one combat the racism, the stereotyping, the profiling, the social repression, or essentially for many with indigenous roots, the relentless practice of colonization? Well, there is one Chicana artist in southern California who, a few years ago, found a unique way to use humor – instead of anger - and irony and satire, to question whether race, or color, or class really actually define our status in the world. Several years ago, Linda Vallejo started finding and collecting artifacts of Americana in antique stores – like pictures, paintings, sculptures, or dolls… and well, I’ll just let her explain. This from a 2015 UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center interview with Linda Vallejo talking about her Make ‘Em All Mexican” series.

UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center interview with Linda Vallejo in 2015.

Linda Vallejo: “When you go out and you’re buying these things, suddenly you realize there’s no brown images out there. There is no brown images. If you find a brown image it may be a little salt and pepper shaker, of a little Indian, right? And even if you find the Vaquero. I found a beautiful Vaquero done in the cracked porcelain from the 1960s. You don’t see brown images. You don’t see those kinds of images. So, it just dawned on me. Well, gee, why don’t I make them brown? Let’s make ‘em brown.”

Ross: So that’s what Linda Vallejo’s been doing. Making em’ all brown. If you get a chance, go to our website and check out some of Linda’s work. She takes well-known Americana images, like photographs, sculptures, or figurines of white people, and transforms them into more Latino-looking characters with skin brown. American Gothic becomes “Mexican Gothic.” Superman becomes “Super Hombre.” Marilyn Monroe becomes “Marielena.” Ben Affleck and Matt Damon holding their Oscars become “Bernardo y Mateo.” You get the idea. Gloria here, says Vallejo’s work reminds of the days when only white people were given all the roles in the movies.

Gorge y Marta (Linda Vallejo)

Gloria: You know, this idea that anytime they wanted to make something about a Latin American you couldn’t cast a Latin American actor. And just in general for others, why not? If it’s just a general role, why can’t he be Mexican? Why can’t he be Japanese? Or anything? It wouldn’t really matter if someone was really good, if the part or the role was good, or if it was written well. We’re starting to see that bend a little now. But yes, it’s been a long road.

Marlon Brando, a white actor, playing the famous Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata in the 1952 film Viva Zapata!

Ross: For Fanny, who grew up in Mexico, Vallejo’s reconfigured images remind her of her childhood impressions of who she thought Americans were – the mostly white people or characters she saw in the movies, or other media.

Fanny: Everything that I watched as little girl, that was American, was all white. So, you grow up with this idea that everyone in the U.S. is all white. And that was a perception we were taught, at least in Mexico. It was an eye-opening opportunity to come to the U.S. and see that it's not that way.

Super Hombre (Linda Vallejo)

Luis: I think with this discussion we’re having about not having representation in films and media and how they would use brown face of black face to perpetuate stereotypes – I think that’s why these pieces by Linda Vallejo are so important. Because, OK, if we’re going to use brown face, we’re going to do it for representation. We’re going to reclaim this image that is very powerful, and we’re going to brown it up, and now it speaks to us too. And so, I love the defiance that she’s using here. And (she) takes certain images here that previously cause a little trauma or harm when you don’t see yourself, and now it’s nice. It feels good.

Ross: As a white guy, I can’t say I’m offended by any Linda Vallejo’s transformation of these artifacts of Americana. In fact, I really love it. I love how Vallejo is so audaciously flipping the script on things and push us into unknown territory. I like how she’s challenging our implicit bias. It’s defiant. It’s kind of radical. And, yeah, I think it can make some of us white people chuckle with a tinge of discomfort. And Vallejo says that’s OK. Here she is again from that 2015 conversation.

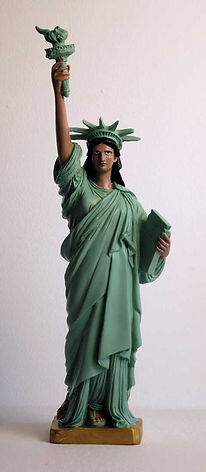

Statue of Liberty (Linda Vallejo)

Vallejo: Yeah, it’s ok to laugh. Please laugh. If you laugh it means you’re getting it. If you laugh it means you’re willing to walk through this doorway with me and talk about the politics of color and the politics of class. And the politics of privilege and the politics of access. If you’re willing to laugh you can get through this door. But if you have a lot of anger the door is shut to you. You end up kind of stuck in the past, with the anger thing. If you can laugh at it you’re on your way to healing, and not take yourself so seriously. And maybe, even like your brownness. Brown is beautiful man!”

Ross: Interestingly, Vallejo’s work does offend some people.

Bernardo Y Mateo (Linda Vallejo)

Moderator: "Have people been offended or discussed their reactions with you?"

Vallejo: "Yeah, they come right at me. One person asked, do you want to be white? [laughing] I said yes I do. Of course, I do, what am I going to say. I wasn’t going to break into tears or anything. Yes, I do. I want the access. I want the privilege. I want the money. I want the power. I want it all. And I want it now! (laughing)"

Ross: Here’s something else that’s fascinating. Vallejo’s brownification of Americana doesn’t necessarily excite some Latinos. Here’s Fanny.

Fanny: I showed one of these images to my family members. And their first impression was, “ahh, no está tan bonito.” You know, white means beautiful. Blue eyes. And suddenly you make it brown, and it’s ohhh. But a Mexican saying that! It’s like, what?! It’s brown like you! Yes, but…

Luis: But that’s a classic sign that they’ve internalized it.

Fanny: Exactly.

Luis: They can’t even appreciate seeing themselves in the image.

Marielena (Linda Vallejo)

Ross: Linda Vallejo herself says she hears similar reactions from Latinos. For example, one questions she says she often gets from Latinos is…

Vallejo: “Why do you make ‘em so dark?”

Moderator: "Was that coming from Latinos?"

Vallejo: "Absolutely. Why do you make ‘em so dark? We’re not that dark. So, the only thing I can come back with is a good joke. Well, I like ‘em short and dark, what are you going to do? (laughing) And all the guys who are short and dark are like hahaha. Thank god someone likes ‘em short and dark. I don’t have an excuse for it. One of the conversations that came up was when I was born I was very fair, and as I got older I got darker and darker and I could feel the love of my family ebbing away. A Latin American actually said that. I mean, this is intense. So, why do you make ‘em so dark is comes actually from within Latino culture, Mexican culture itself. It’s not something that’s outside. It’s not one culture against another, it’s one culture against itself.”

Vallejo's Make ‘Em All Mexican solo exhibition, at the Clemente Soto Velez Cultural Center, Abrazo Interno Gallery, New York, NY (lindavallejo.com)

Ross: So, what should we take away from these conversations about this internalized negativity about a brown complexion versus a white one? I’d prefer to live in a world where everyone can be beautiful – can think of themselves as beautiful – no matter their skin color. I’d prefer to live in a world with a lot less fear and hate, and instead live in a world with much more love and acceptance, and compassion. What can we all do to make our society more equitable and just, and a kinder place for everyone? I want to send you off with this bit of tape, with these thoughts and advice. Here’s Fanny, followed by Jorge, Xris, and then Luis.

Ross: I’m wondering when we turn this into a podcast, because this is an English podcast, and people listening to this from the majority white ethnic community, what advice or thoughts would you have for them? What can we change that’s not happening now?

Fanny: I was thinking about wearing a shirt saying ask me who I am. I don’t mind, really. I’d rather you ask me than make assumptions.

Jorge: What I encourage people to do, especially Latinos in our community, is go out of their way to reach out, and let themselves be known. Because it’s much harder to demonize or stereotype groups of people if you know them. If you realize, he, this is my neighbor. This is my son’s school friend. This person works at the bank I go to. Once you put a face, and you have a name, and an identity you can put on them, then it’s much harder to put them in a little box. So, I think it’s part of our responsibility, much like Fanny has said, to put ourselves out there and be known.

Xris: I agree with that. It’s part of the reason I’m in school, to begin with. To educate myself on what things out there exist and how I can incorporate myself into it. What kinds of stores can I tell, that can be pushed statewide, nationwide, or worldwide. Where can I see my perspective or my stories being told? At the same time, there needs to be certain training or exposure for those already in the institution to reach out. Because a lot of times I feel like we will be trying to tell our story or do something, and who is listening? You know, it has to be in both directions. But I do completely agree we have to put ourselves out there. But who is going to be the ones listening to us, and go out into our communities, and listen to our needs? Part of the issue is that we simply may not understand the system that is supposedly representing us. Our communities may not understand because of language barriers. They may not understand because of connection barriers, class issues. There are so many different identities that play into that. But if somebody isn’t willing to go across those lines and see what the community needs, it’s simply not going to happen. I am grateful for those political representatives we have in the House and Senate who do that. There are many women of color who are Senators, and that’s awesome. We just need more of that. We need some kind of system that is officially sanctioned by the government, in Spanish for example, in Spanglish. Where people can read it and understand it in simple terms.

Luis: For me, what advice I would give listeners who don’t identify as Latino or Mexican or Chicano, the one thing I encourage is quality interactions with other people who are different than you. There are a couple ground rules for that. Don’t approach it as a checklist or a box. Oh, I went to a diversity training, I know what people who are different are. Check. No. The second would be - and this is the hardest one for every person - when you do go to some cultural event or will be around people who are different than you, check your ego at the door. We tend to view the world through our cultural lens. And we view it as the dominant point of view, right? When we go to these other spaces, we need to go as students to learn. Because that’s how we truly grow as people. So, when you go and say in my culture this means that, and this has that value, well, I’m going to occupy this space, how do they view it? And I need to respect that. With those rules in mind, I think those interactions will lead to positive benefits, and you’ll start to see other people as human. Because I think the root issue with a lot of the stories we’re sharing are these ideologies that dehumanize us. So, once you start to see people of color as humans, and you have quality interactions that will challenge your way of thinking, leading to growth, and ultimately truly understanding others because you have firsthand experience, not just because you read it in a book or saw a documentary.

"Pocho" by the Chicano musicians Los Alacranes, Ramon “Chunky” Sanchez and his brother Ricardo Sanchez. Ramon Sanchez passed away a few years ago. His brother still lives in San Diego. Learn more about their work here.

~ ~ ~

Credits:

Thanks to our commentators Xris Macias, Luis Lopez, and Jorge Rodriguez, Gloria Gonzalez Cook, and Fanny Blauer. Episode produced and edited by Ross Chambless; Thanks to KPCW in Park City for the studio space; The music you heard in this episode comes from the Gypsy Kings, El Chicano, Latin Playboys, Cheech Marin, Gustavo Santaolalla, Antonio Pinto, Alejandra Guzman, Metalachi, Elliot Goldenthal, Chicano Batman, and , of course, Los Alacranes.

Engage with Us:

Has anyone ever made you feel like you don’t belong in the U.S., even though you were born in this country? How did you react, or how did you wish you responded? And, what do you think of Linda Vallejo’s work? What does it make you think about? How does it make you feel? And do you have anything to add to our conversation about the internalization of negative feelings some Latinos have about their own brownness? How do you think more people of color and Latinos can overcome these attitudes?