Episode 8:

The American Invasion

Mexico and the United States tend to remember their 1847 conflict, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo very differently. More than 500 thousand square miles of land - which became California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming - became American property. To this day, generally speaking, Mexicans still consider the land unjustly stolen. On the other hand, many Americans still might claim the land was righteously obtained. While art was a powerful tool for convincing American people that conquering the frontier and claiming Mexico's territory was America's divine destiny, art remains an important means for remembering the conflict for both sides.

Ross Chambless: If you’ve been listening to earlier episodes of this podcast you already know that the idea came from a class about Mexican art and history that Fanny Blauer and Susan Vogel teach to groups of older American adults. Fanny, who grew up in Mexico, says her students tend to get uncomfortable when the subject of the Mexican-American War comes up. She says in Mexico, they have a different name for it.

Fanny Blauer: It’s called the American Invasion.

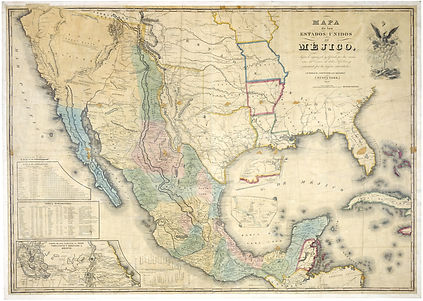

This Disturnell map of of Mexico as it was in 1847 was appended to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. According to the U.S. National Archives, "On February 2, 1848, a Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement was signed at Guadalupe Hidalgo, thus terminating the Mexican-American War."

Ross: Fanny has brought a 5th grade history textbook into our studio. It’s produced by the Mexican government, that explains – if you understand Spanish – what happened from the Mexican perspective.

Fanny: I think at the beginning of your education in elementary school, you are growing to dislike Americans in many ways. We carry this heritage of – they took half of our territory!

A quick summary of the history: "Westward Expansion: Crash Course US History #24"

The History Channel documentary "The Mexican American War" hosted by Oscar De La Hoya.

Ross: Here’s just a reminder of why this conflict was important – even though it happened 170 years ago – and why the agreement that followed – the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo – that was created under President James Polk, changed everything between America and Mexico. This is from a History Channel documentary.

“For a price of 15 million dollars, half the original offer made two years earlier, Polk received what he long desired: A Texas-Mexico border at the Rio Grande, and Mexico’s northern territories. Today that land includes the states of California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. More than 500 thousand square miles. Nearly half of Mexico’s former territory.”

Ross: One of the images young Mexican students see in their history textbooks when they learn about this war is an 1851 painting by Carl Nebel.

A depiction of the American occupation of Mexico City in September 1847, by George Wilkins Kendall, founder and editor of the New Orleans Picayune. The painting was published in 1851, as part of a collection of works titled The War Between the United States and Mexico, Illustrated.

Susan Vogel: It’s of the Zócalo in Mexico City. There’s the cathedral. It looks like downtown Mexico City, and there are troops marching in. And when we show this to students, we ask: anything out of place here? It takes them a while, and then they see a U.S. flag flying over the National Palace. So, I ask what would it be like if you went to Washington D.C. and see the Canadian flag flying over the White House? And often they say, well, that would be rude.

Ross: To add insult to injury, in September 1847 when American troops hoisted their flag on Mexico’s capitol, it was a couple days before Mexico’s national celebration of Independence from Spain. Fanny who is now a U.S. citizen has studied the conflict. She says now her understanding is more nuanced.

Fanny: I think Mexico played huge role in losing this part of the territory. The way the corrupted system was built with president Santa Anna and the relationships they had with Mexico. And how Texas always considered themselves an independent territory. All these factors played a huge role. The fact that President Polk, his idea of moving towards the West, taking advantage of this, and Mexico is the neighbor that will have to suffer the consequences. Everything comes together, not only the invasion.

Here is a scene from the 1939 film El cementerio de las águilas, "The Cemetery of Eagles" about the battle for Mexico City, as portrayed from the Mexican point of view.

Ross: This is from a 1939 Mexican film – the Cemetery of Eagles – showing the fall of Mexico City, and American soldiers admiring the bravery of the young Mexicans they've just killed. In this episode, we’re talking about art and the Mexican-American War, or the American Invasion – depending on what version of the story you’ve heard.

Today in Mexico, that particular American invasion – there were actually several – is remembered with a national holiday: September 13th. They even have a national monument to mark a decisive battle.

Fanny: So, as part of that battle going on Mexico City when American troops arrived. There was a big battle on the hill of Chapultepec.

An illustration of the Battle of Chapultepec. Public Domain

Ross: As the story goes, as American soldiers closed in on the city, there were half a dozen teenage Mexican boys who fighting to the bitter end. And one of them wrapped himself in the Mexican flag, to save it from being captured, and threw himself off the edge of a tower to his death.

Fanny: This story of the "Niños héroes" has become legendary, I found. There’s a lot of material that is extremely controversial as far as this concept of these heroes, these boys, have been politicized throughout the history of Mexico.

September 13 is a national holiday in Mexico to commemorate Niños Héroes, a key part of Mexico's patriotic folklore. The Monument for the Niños Héroes celebrates six brave teenage Mexican soldiers who died defending Mexico City's Chapultepec Castle from U.S. forces.

Ross: The monument for Niños Héroes – or Child Heroes – celebrates Mexican bravery and sacrifice in a war that they lost. They even hold annual reenactment ceremonies you can see on YouTube.

Here is a video showing the annual reenactment to celebrate Niños Héroes.

Susan: Niños Héroes represents the idea that Mexico’s identity is based on fighting off invaders. And we don’t think about that at all here.

Ross: If I think about the cultural identity I grew up with, it was celebrated in an American holiday, every July 24th. That’s Pioneer Day in Utah, the day Mormon Pioneers settled in Salt Lake City. And every year in a Days of ’47 Parade, a group of men in period costumes and muskets march down state street as the Mormon Battalion. That was a group of Mormon soldiers who went off to join the war against Mexico.

The March of the Mormon Battalion (1986), summarizes the history of the Mormon Battalion's march during the Mexican-American War in 1846.

Clip from The March of the Mormon Battalion: “Even after many years, these volunteer patriots realized their service to God, country, and family helped to secure a vast new territory for their country, through their march. The March of the Mormon battalion.”

Ross: But there’s this other battalion from that Mexican-American conflict that I’d never heard about.

A scene from "One Man's Hero" (1999), a film about the San Patricios (The St. Patrick's Battalion), a group of Irish immigrants who deserted the U.S. army and fought with the Mexicans instead.

Ross: "One Man’s Hero” is the 1999 film about the St. Patrick’s Battalion – or the San Patricios - a group of Irish-Catholic immigrants who deserted the American army and fought with the Mexicans instead.

Fanny: When the Irish saw they were being discriminated for their religion, their accents and being from Ireland. What was happening here was the same that was happening at home. So, they moved to the Mexican side, and they fought.

Ross: The Mexicans and the Irish shared the Catholic faith, and apparently, the Mexicans treated them better. But in the end, the Irish turncoats were captured, and hung to death, and all but erased it seems from American memory. But they’re still celebrated in Mexico, and with an obscure modern folk ballad.

The St. Patrick Battalion, by David Rovics, American indie singer/songwriter and anarchist.

SONG: “We formed the St. Patrick battalion, and we fought on the Mexican side. We formed the St. Patrick battalion, and we fought on the Mexican side…”

Ross: I don’t think it’s that Americans have tried to forget that our country invaded Mexico and took their land, and that’s why we don’t remember it or talk about. It may just be something that culturally, we’re not proud to remember. Even in that History Channel documentary, there’s a tinge of guilt.

History Channel Documentary: "This was the War Abe Lincoln called Unconstitutional. And Ulysses S Grant labeled one of the most unjust wars ever waged. But the president who waged it, James Polk, believed the U.S. had ample cause.”

"Battle of Churubusco" by J. Cameron, published by Nathaniel Currier. It was during this battle that the San Patricios made their last stand against the American forces.

Luis Lopez: Well, I can share my experience with this. I grew up in California. And at school we learned about the Mexican-American War. I come home, and say hey dad, today we learned about the Mexican-American War. And he says, ‘What Mexican-American War’. And said, yeah, mutual combat between two adversaries over some kind of dispute. And he said, No. Mexico was already basically weak, beaten up, trying to recover. And they just came in and took it. Right, so I got a completely different narrative at home. I wasn’t really sure where I fell. Do I agree more invasion, with that terminology. Or do I agree with “Mexican-American War”. But at the age of 13, I realized that what schools were teaching wasn’t necessarily the whole truth. So as a Chicano, that definitely contributed to some feelings later on about, well, now I’m in this space. I have no control over what happened. But there is a sense of “nativeness” to this land. Being Mexicano as well, history lets me know we here prior to these disputes. So that made another connection for me.

Susan: I grew up with this idea that we all, our relatives and ancestor came West for the great opportunities and to build our country. Grew up singing the song about the U.S. from Sea to shining sea, and very proud of this heritage of the United States. We definitely learned that during this expansion there were some terrible things done regarding Native Americans. But other than that it was just proud of this pioneer heritage, and the values of expanding this country and building it, the California gold rush, and all of things that built the country we have now.

A small picture, with a big idea. John Gast's "American Progress," (1872), was widely disseminated as a commercial color print and conveyed a range of ideas about the frontier in nineteenth-century America.

Ross: Let’s get back to the art, for a second. If you could name only one image that most profoundly shaped American cultural identity during the late 1800s, what would it be? It might be this one, that’s pretty commonly found in American history textbooks.

Susan: It’s called American Progress.

Ross: It was painted in 1872 by John Gast.

Susan: It looks huge! And when I first looked at this I thought it must be a mural, it’s so powerful.

Ross: In fact, it's small, it’s only 12 inches by 16 inches.

Susan: It’s been reproduced many times. It was commissioned by the publisher of a fashionable Western travel guide. And reproduced in magazines and as a poster.

Ross: It’s often called the Manifest Destiny image. It’s a rectangular painting of an imagined landscape of the American West.

A short explanation of the concept of Manifest Destiny.

Susan: There’s movement in this painting from right to left, mainly because the main subject of the painting is this blonde, white skinned, scantily clad angelic image, floating through the air from the light on the right to the darkness on the left.

Ross: This angelic figure lady is holding a book in her right hand.

Susan: And in her left hand, she is trailing behind her wires. This could be telegraph wires. Or it could be Google fiber, I don’t know. It represents the expansion of technology I think.

Ross: Below this floating woman railroad tracks are being laid, horse-drawn stagecoaches are driving forward, and white European people are in the forefront, advancing Westward toward the left side, which is the dark, cloudy, foreboding Western frontier – there we see Indians and buffalo and other wild animals being driven out.

Luis: I think this is symbolic of the lens in which history is written.Text throughout schools and different curriculums kind of portrays history in this same way. We see it from elementary all the way to high school, where settlers are seen as heroes, and doing the work of God. And they downplay the atrocities that happened to native peoples. So with this image of this woman looking angelic and heavenly, she doesn’t look menacing or aggressive. She’s just gracefully gliding over these people down here, protecting them. It almost seems naturally the native Americans and animals are on their own getting out of the way. And that’s not how things went down.

On the walls and ceiling above the Utah capitol rotunda are a series of murals depicting the pioneer settlement of Utah. This panel portrays the people who lived in Utah before the Mormons: Native Americans, Spanish explorers, and Mexicans. The images were painted in the 1930s.

Ross: Whenever I stand under the rotunda of the Utah state capitol and look up, I see images that tell stories not unlike John Gast’s American Progress. These large public murals tell the state’s official narrative about this place. Most of the mural panels depict an industrious group of pioneers – their skin as white as mine – intrepidly building a new home out of the wilderness. In one panel a group of men are planting an American flag atop Ensign Peak. But what interests me most is a single panel showing the backs of four brown-skinned Mexican-looking men wearing sombreros with a donkey. Next to them stands two Spanish missionaries, and next to them, a solitary Native American man, standing, almost pushed out of the frame. Each of these men are lumped into the same panel, even though they inhabited this land at completely different times. They’re all looking out across the horizon towards Utah Lake.

I wonder what they’re thinking.

I wonder what stories they would tell about this place.

I wonder if they saw those white pioneers as illegal immigrants coming into Mexico.

Another romantic portrayal of Mormon pioneer settlement of Utah, which was then Mexico, in the Utah capitol rotunda.

Danny Quintana: Most of history is the story written by the people who write it. And if you don’t look for other sources of history, whether they are oral histories or the indigenous communities and their side of it you’re not going to get a broader perspective. I’m a writer and environmental activist. I practice law, so I can afford my nefarious activities.

Ross: Danny claims his roots all the way back to Spanish settlers in 1598 who colonized New Mexico.

Quintana: Well, when I was growing up I rejected that entire view of history because my early childhood was in New Mexico and Spanish was my first language, 16th century castillian Spanish. And I knew my history before I came to Utah. And I always looked at history as West looking east. What are these people doing invading our lands? So, when I would see these pictures and the history being taught, I questioned every single aspect of it and studied history on my own. And I didn’t believe any of that. I never bought into the whole mythology of Manifest Destiny.

A quick summary of the 1999 film Ravenous. (Thank you to Renegade Cut, Jack Conte).

Ross: In some ways my own perception of Manifest Destiny is shaped by a more contemporary critique. There’s a 1999 film called Ravenous. It’s kind of an obscure, black-comedy horror movie, and it’s gruesome – it’s about cannibalism. It takes place during the Mexican-American war at an isolated American army outpost in the Sierra Mountains of California. And near the end, a few of men are overtaken by an infectious, insatiable craving to kill and eat other people to survive.

Scene from Ravenous: “Manifest destiny. Westward expansion. You know come April, it all start again. Thousands of gold hungry Americans will travel over those mountains on their way to new lives passing through right through here. We won’t kill indiscriminately. No. Selectively.”

Here's an intriguing mapping project by Michael Porath. Manifest Destiny tells the story of the United States in 141 maps, from 1789 to the present.

Ross: This story is an allegory of Manifest Destiny, a critique of America’s unquenchable desire to expand and grab as much land as possible in the 19th century. There’s no floating angel of righteous entitlement here. Just unbridled consumption – cannibalism – a crisis of morality with which the American soldiers must reconcile. For me, this film, John Gast’s American Progress, and even the murals painted above us in the Utah capitol rotunda skirt around some very awkward and uncomfortable questions that still linger: Who was here first? And, has the taking of Mexico’s land ever truly been settled? And if not, what do we do about it?

Fanny: I mean, who was here first? When we see that perspective. As a global human perspective, it becomes a very politicized language, in terms of how we want to make ourselves. And for me, the concept of Manifest Destiny, I never heard about this during my childhood. It wasn’t until I came to the U.S., that I learned. I learned in a way that Santa Anna was a very stupid Mexican president that allowed that to happen. That’s what I learned.

Luis: I think it definitely affects students, people having to live with this every day. When you hear about it, see paintings. It’s only giving you this one narrative, that deep down you know is not the whole truth. And it’s portraying your people, I identify with my indigenous ancestry, it portrays us in a certain way that definitely doesn’t contribute to your self-esteem, your self-image. You kind of internalize these things. We ask ourselves what effects this has on students and people in general.

Here are some recent memes that parody the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. An advertisement for Absolut vodka, and a critique of Donald Trump's plan to have Mexico pay for a border all on the southern border, credited to Dianne Wing @DianneWing2.

Ross: Susan here, grew up in Utah just like me, but as a teenager she spent more time in Mexico.

Susan: I started going to Mexico when I was 17, and I started getting a different point of view, or at least learning different points of view. It was pretty startling. I went from a class at the University of Texas, El Paso, where the teacher said in my class the Eagle flies, and the flag waves, and if you don’t like it take another class. And then I landed in La UNAM, the University in Mexico City, learning about things I’d never heard of in Mexico. Socialismo, Marxismo, Comunismo. Suddenly my mind exploded, I thought, oh my gosh, I get to learn about all these things throughout the world! It was a huge and exciting thing to learn about different countries and cultures...

... But, this hit me personally when I was married to a Mexican. Had a baby who is half Mexican. We would invite her grandma up to visit from Mexico City, and I would say “Bienvenidos Utah,” “Welcome to Utah!” And she would say “which you stole from us!” So, I thought, what? I knew intellectually the history, but I didn’t realize it was so alive.

Image of an official state timeline at the Utah capitol. For some reason it skips any mention of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which allowed for the pioneers to make a claim for the "state of Deseret", which was eventually whittled down to the state of Utah.

Susan: I recently read an article about NAFTA and all the things going on politically now, and you can’t negotiate a trade agreement unless you understand the role of history. And so, from the Mexican point of view, renegotiating NAFTA, the perspective is the Mexican-American War, 1846, a trumped-up border dispute that ended up with U.S. soldiers occupying the capitol of Mexico and forcing the countries leaders to hand over half the country’s territory. The Mexican Revolution in 1910 when the U.S. Ambassador helped overthrow the Mexican president. The U.S. invasion of Mexico in 1914. All of these historic events are very relevant to the current situation...

... And [the article] quoted the Mexican ambassador to the U.S. saying Mexicans live with their history every day. I think that’s something we don’t do, and we overlook when dealing with other countries.

Ross: The images we discussed in this episode live in the website and home for this podcast www.artesmexut.org. You can also find some of the links to the films we mentioned and discussed.

~ ~ ~

Credits:

Thanks to our commentators Susan Vogel, Fanny Guadalupe Blauer, Luis Lopez, and Danny Quintana; Episode produced and edited by Ross Chambless; Thanks to KCPW 88.3 FM for the studio space; Music credit: Elliot Goldenthal, Antonio Pinto, Gustavo Santaolalla , Damon Albarn and Michael Nyman (Ravenous soundtrack), and David Rovics wrote the song about the St. Patrick’s Battalion, and this cover of This Land is Your Land by Chicano Batman. This podcast is made possible thanks to Utah Humanities.

Engage with Us:

What were you taught about the Mexican-American War? How about the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo? Why do you think some stories from the conflict have been romanticized, while other stories have been seemingly forgotten? How do you think this history shapes the contemporary identities of Mexicans and Americans?